By Katie Thomas

“Wellness” is a hot buzzword in the industry right now because it falls at the center of an important Venn diagram: It’s top of mind for consumers and it’s an area chain drug leaders are watching to increase their relevance with consumers. Many leaders believe, or at least hope, that the broad topic of wellness could be a solution that drives traffic into chain drug stores and increases basket size.

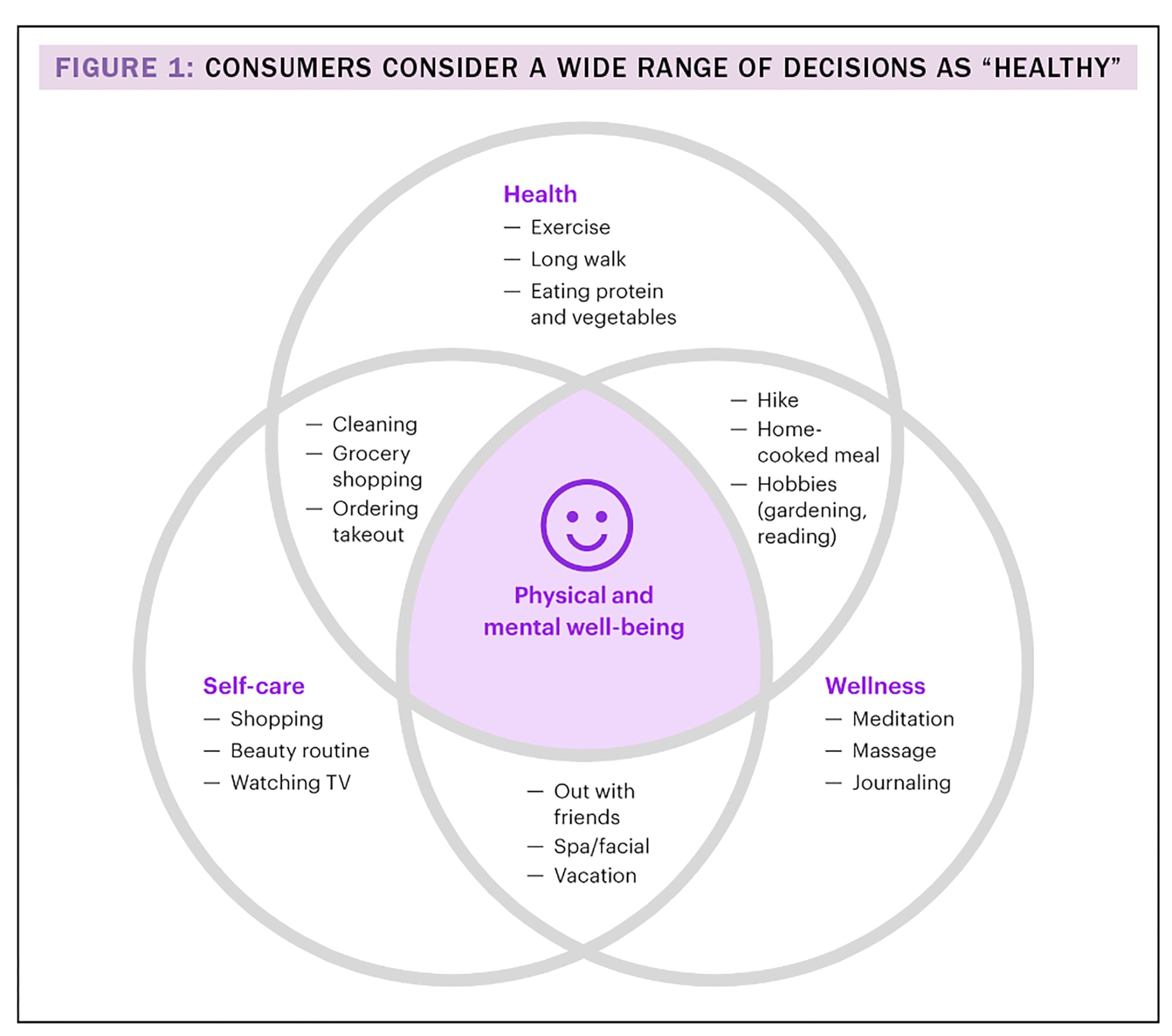

But what does wellness really mean? What about its cousins, health and self-care? New research from the Kearney Consumer Institute finds that those definitions vary widely from person to person. Consumers define health and wellness for themselves and are not looking for “education” from brands or retailers. Everyone’s wellness journey is different: Does self-care mean indulging in a treat or getting extra sleep? Is a glass of wine bad or one of the day’s simple pleasures? That broad umbrella could be an advantage for chain drug stores, with products on shelves ranging from spa masks to vitamins.

In this article, we’ll review recent Kearney Consumer Institute research to explore the questions:

• What do consumers say about wellness? And what does consumer behavior actually look like?

• What kinds of health and wellness support are consumers looking for from brands?

• What could “health and wellness” mean for chain drug?

Is health and wellness really a trend? (What do consumers say about wellness? And what does consumer behavior look like?)

Our first finding: Forget the trend of the moment. Health and wellness has always been on trend — from fad diets to trendy fitness classes to superfoods and beauty as health. Conversations about trends do not capture the complexity, nuance or inherent conflicts for individual consumers.

As options and access have expanded, so have consumers’ choices. As a result, the concept of health is rife with confusion, conflict and moving targets.

Health is both a reality and an aspiration for most consumers. We tend to focus on statistics that show that consumers are trying to be healthier — our own study validates that, with 89% saying they want to be healthier. However, 76% of consumers say they live a healthy lifestyle. So despite the theoretical desire to be even healthier, most consumers say they are already doing just fine.

Similarly, consumers claim that health is a top priority, but there’s no one right answer. We asked consumers: “What do you do to try to be healthy?” and got a wide range of responses:

• Take vitamins and supplements: 60%.

• Get 7 to 9 hours of sleep: 59%.

• Exercise: 58%.

• Eat healthy food: 57%.

• Go to the doctor: 55%.

• Take prescribed medications: 47%.

Health is personal, emotional and complicated. As the definition of health continues to blur, consumers can frame many different decisions as healthy, from cooking at home to ordering takeout, from meditating to watching TV (see figure 1).

Do consumers need to be educated on health? (What kinds of health and wellness support are consumers looking for from brands?)

Consumers are not looking to brands for education about health. In our study, 85% contend they know how to make healthy choices, and only 17% of consumers said they don’t know how to be healthier or find it confusing.

Consider a supposedly simple example: Most consumers know that a salad is a healthier choice than a burger and fries. But sometimes they may not be able — or may not want — to make that choice. And as the definitions of health and wellness evolve and expand, this choice only gets more complex. For instance, maybe the burger and fries is during a much needed night out with friends, whose self-care benefits far outweigh the seemingly healthier choice. Or perhaps the consumer is a subscriber to the carnivore diet, and truly believes the burger (sans fries) is the better choice.

Whatever the explanation may be, each individual consumer makes their own decisions, trade-offs and rationalizations. Therefore, the role of brands and retailers is to support consumers’ choices based on each consumer’s definition of what’s healthy, and also allow them to choose when they want to be healthy — and when they don’t (ever cringed at calorie counts on a menu?). Consumers do not tend to see individual brands, and the claims made on-pack or in advertising, as the source of truth on health. They are evaluating each decision in the broader context of their lives.

Instead of chasing the trendy product or category of the moment, it’s in brands’ best interest to think more broadly and holistically about health and wellness. Probing into the specifics of a brand’s consumers and their relationship with health is a great start. What are their top health priorities, and what do they often sacrifice? What are their most common trade-offs and commonalities? When do they expand the definition of health to mask a choice as healthy?

What could ‘health and wellness’ mean for chain drug?

A broad definition of health and wellness is good news for chain drug stores. Consumers come to chain drug retailers to buy everything from prescription drugs to nail polish to potato chips. Any product category could fall into the health, wellness or self-care category for an individual consumer.

We see two potential paths for chain drug stores to take advantage of the current broad category of health and wellness:

• Optimize merchandise throughout the store — This simple path marries wellness with categories that already exist in the store. Consider what consumers are already coming in to do and buy, and connect those shopping trips with self-care. A retailer might even deemphasize health and lean more heavily into self-care, which folds better into the high-margin beauty category. In our survey, 53% of consumers said buying a new beauty product is self-care (over the other options of health, wellness and indulgence).

• Retailers could expand shoppers’ access to self-care purchases by offering quick pick-me-up drink options, highlighting a wider array of new nail polish colors or spa masks, or expanding even further into wellness and self-care serving offerings. Ultimately, given consumers are able to educate themselves, improving access and optimizing choice instead of investing in claims or short-lived trends can be impactful.

• Try to win in one category of health and wellness — The other path is more ambitious. Because so many health and wellness categories are nuanced and shifting, chain drug retailers have ample opportunity to claim, own and win in a specific slice of the category.

For example, sleep is one of the most prioritized categories of health for consumers, but when stress occurs, sleep is the first category to suffer. It’s also a category that no one seems to be winning, yet it’s often bucketed into the broader health and wellness or supplement aisle, or shifted all the way to mattress and linen manufacturers. Chain drug stores have the opportunity to support shoppers’ sleep choices through new services such as sleep consultations, expanded sleep products or heightened merchandising attention for existing sleep solutions in the store.

Our research tells us that consumers do not want brands to define health and wellness. Instead, they want helpful support as they make a broad range of healthy choices. Try not to get lost in the trends; instead, take a step back and understand health and wellness as a full and varied lifestyle, full of personal trade-offs.

Katie Thomas is the global lead of the Kearney Consumer Institute at Kearney. She can be reached at Katie.Thomas@kearney.com