By Lari Harding

Retail pharmacies are entering a new era of financial complexity as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) begins to reshape Medicare drug pricing. With Maximum Fair Prices (MFPs), shifting receivable timelines, and strategic accounting decisions ahead, pharmacies must prepare for new working capital pressures and updated financial reporting practices.

What the IRA means for Medicare and drug pricing

The IRA is a 2022 U.S. law that aims to lower prescription drug costs, reduce the federal deficit and invest in clean energy. For Medicare, it introduces historic reforms like drug price negotiation, a $2,000 annual cap on Part D out-of-pocket costs, and $0 co-pays for ACIP-recommended vaccines. It also penalizes drug makers for raising prices faster than inflation to protect patients from excessive cost increases.

The MFP within the IRA is a mechanism to limit drug prices for Medicare beneficiaries. It essentially sets a ceiling on what manufacturers can charge for certain drugs selected for price negotiation.

The first round of negotiated prices for selected Medicare Part D drugs will take effect on January 1, 2026. These MFPs will apply to the following 10 drugs: Eliquis, Jardiance, Xarelto, Januvia, Farxiga, Entresto, Enbrel, Imbruvica, Stelara and Fiasp/NovoLog.

On January 17, 2025, CMS announced the selection of 15 additional drugs for the second cycle of negotiations, including: Ozempic, Rybelsus, Wegovy, Trelegy Ellipta, Xtandi, Pomalyst, Ibrance, Ofev, Linzess, Calquence, Austedo, Austedo XR, Breo Ellipta, Tradjenta, Xifaxan, Vraylar, Janumet, Janumet XR and Otezla. Negotiated prices for these drugs will take effect on January 1, 2027.

Three financial implications for retail pharmacies

For retail pharmacies, there are three major financial implications.

• First, pharmacies must plan for increases in working capital requirements.

• Second, they must ensure systems are in place to manage a secondary receivable on all IRA-impacted prescriptions to recover all revenue due, or another tracking system. This includes closely managing each script to avoid losses on fulfillment.

• Third, pharmacy financial statements will need to address how manufacturer payments are classified — either as revenue or as a reduction to Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). Pharmacies will need to produce new accounting transactions for all IRA prescriptions.

Based on data from Inmar Intelligence, the average retail pharmacy’s sales for drugs included in 2026 will vary based on the percentage of Medicare D patients served, but may range from 5% to 15%, using historical filling patterns. In 2027, that percentage may jump to 10% to 30%. The projected increase in the number of days it will take to get paid on the secondary receivable coming from pharmaceutical companies is seven to 30 days. The average per-pharmacy impact on working capital requirements in 2026 is estimated to range from $30,000 to $50,000. In 2027, this will increase again.

The working capital requirements alone will put a new set of financial pressures on retail pharmacy. Over the last 10 years, margins have been squeezed by PBM consolidation, Medicare DIR fees, regulatory requirements and changes in front-store shopping behavior. These pressures have led to closures across independent and large-chain pharmacies. The added burden of IRA-related receivables has the potential to accelerate this trend.

A primary manufacturer may meet its statutory obligation under section 1193(a)(3) of the act by retrospectively transmitting payment for the difference between the dispensing entity’s acquisition cost and the MFP (the MFP refund amount), within the 14-day prompt MFP payment window. Pharmacies will need to record a secondary receivable for each prescription filled to ensure payment is received or develop another tracking system.

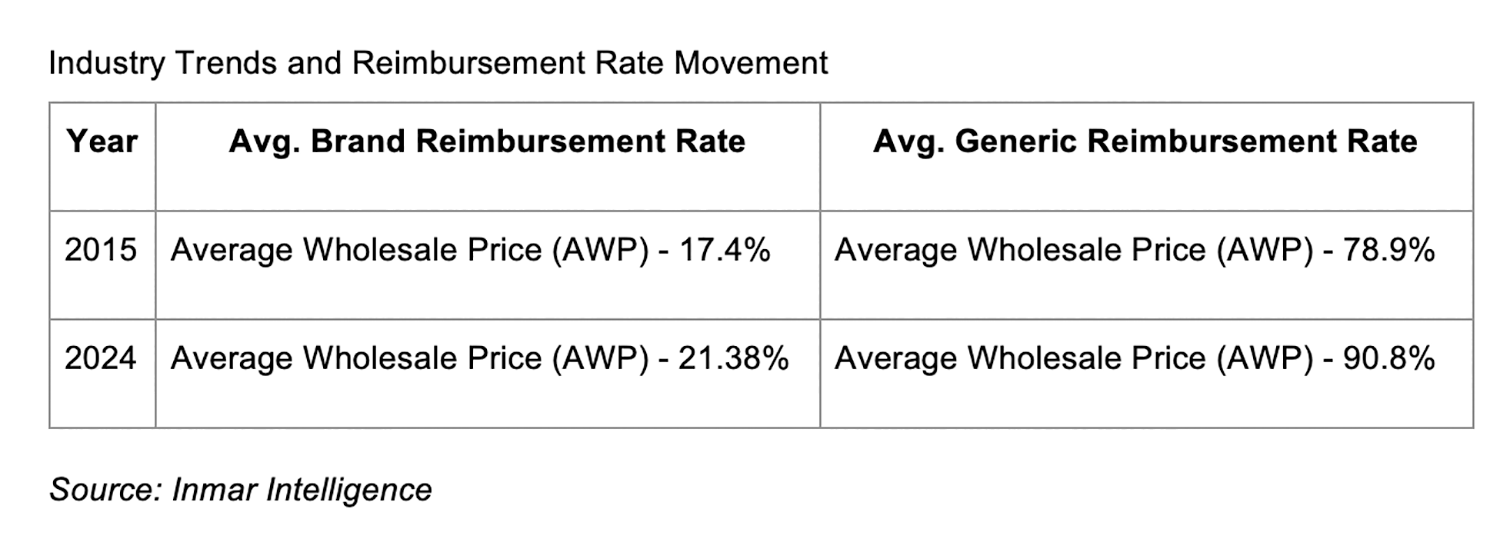

Inmar data demonstrates that the average brand reimbursement rate for all drugs is less than wholesale acquisition cost (WAC). If retail pharmacies ultimately get reimbursed by PBMs and manufacturers in total at 100% of WAC, this would be a bright spot — as overall reimbursement would increase, albeit with longer payment timelines.

Accounting for MFP: revenue vs.

COGS debate

There has been much discussion in the industry on accounting practices for the IRA. From a business perspective, many retail pharmacies want to treat manufacturer payments as revenue. Doing so avoids significant reductions in reported sales, which influence investor reporting and internal performance incentives. A drop in sales could cause cascading operational adjustments.

Alternatively, treating manufacturer payments as a rebate against COGS aligns with the IRA’s intent to lower drug costs for Medicare. If the pharmacy pays full price to the wholesaler and then receives a direct payment from the manufacturer (or through CMS), the MFP payment may function as a rebate — even if the manufacturer is not the direct seller. GAAP generally views such reimbursements as a reduction to COGS.

However, under the U.S. GAAP, the accounting treatment of price concessions such as the MFP under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) requires judgment and depends on the nature of the transaction and the entity’s role in the pharmaceutical supply chain. A key distinction is who controls the sale. If the pharmacy negotiates pricing through PBM contracts and controls the transaction, then the MFP should be included in revenue. If the MFP is reimbursed post-sale and more akin to a vendor rebate, then COGS treatment may be more appropriate.

Clarifying the role of PBMs and

payment timing

Pharmacies (or their Pharmacy Services Administration Organization, or PSAO) negotiate directly with PBMs. Each PBM contract with each pharmacy chain is different. PBMs serving Medicare assemble pharmacy networks that help fulfill their obligations to CMS. So, the pharmacy does control their revenue. MFP is part of the total consideration for the sale. In this case the manufacturer payment is a settlement mechanism, not a vendor incentive. The reason that manufacturers pay pharmacies later and in separate transactions is because they must first receive data from the PBM.

Based on this, pharmacies negotiate directly with PBMs, including those serving Medicare plans. Each contract is unique, and pharmacies retain pricing control. Manufacturers reimburse pharmacies after the fact — not because the payment is disconnected from the sale, but due to the administrative timeline. This operational flow means that pharmacies determine their expected revenue at the point of sale, with the MFP included as part of the expected consideration. In this case, MFP payments should be included as revenue.

Preparing for the IRA’s financial impact

Retail pharmacies, whether privately held or publicly traded, must consult with auditors, document procedures and set up accounting processes that support the method most aligned with GAAP for their structure, either as revenue or COGS adjustments.

The future implications of the IRA infrastructure are also significant. As more drugs are named annually, the percentage of revenue subject to these changes will grow. Some anticipate this platform could enable further pricing policies like the Most Favored Nations Executive Order. While MFN and IRA differ in their legal and policy origins, they share technical, operational and enforcement similarities. For stakeholders like pharmacies, PBMs and manufacturers, this suggests that investments in IRA compliance will likely remain relevant under future drug pricing policies, including MFN models. While the future remains uncertain, pharmacies must prepare now for IRA-related changes effective January 1, 2026.

Lari Harding is senior vice president of industry affairs and strategic partnerships at Inmar Intelligence.