Momentum for PBM reform was among the hot topics at a pharmacy roundtable conducted by Chain Drug Review during the NACDS Total Store Expo this summer in San Diego. Retailers, suppliers and industry advocates also discussed the prospects for standardization for prescription reimbursement, and for an expanded scope of practice for pharmacists, with remuneration for clinical services. Also addressed were the implications of generative AI, including whether it can ever replace pharmacists. Participants also explored the potential for linking pharmacy and primary care, and the industry’s progress toward establishing value-based care as opposed to the current fee-for-service business model.

PANELISTS

Steve Anderson, President and CEO, NACDS

Jason Ausili, Head of Pharmacy Transformation, EnlivenHealth

Lari Harding, Senior Vice President of Client Development, Inmar

Todd Huseby, Partner and Americas Consumer Healthcare Lead, Kearney

Nancy Lyons, Vice President, Chief Pharmacy Officer, Health Mart by McKesson

Jim Rotsart, President – US, MedAdvisor Solutions

Dain Rusk, Vice President of Pharmacy, Publix

Sean Spears, Senior Director of Trade and Pharmacy Relations, Eisai

Karen Staniforth, Chief Pharmacy Officer, Rite Aid

Brian Sullivan, Principal – Pharmacy Solutions, KNAPP

Lisa Tomic, Vice President of Pharmacy Operations, Walgreens

Mike Wysong, CEO of CARE Pharmacies and NACDS chairman

Jennifer Zilka, President, Good Neighbor Pharmacy

MODERATOR

Jeffrey Woldt, Editor-in-Chief, Chain Drug Review

WOLDT: To start the discussion, I’ll ask Mike, as chairman of NACDS, to share his views on his first few months in that role, and where he thinks the industry is headed.

Mike Wysong, CARE Pharmacies

WYSONG: It’s been an action-packed four months. Candidly, I think this is certainly like when I took over Care Pharmacies. Your experiences and your expectations sometimes aren’t exactly what you think they’re going to be. And so while I took over the chairmanship, I was super-honored to take and assume that responsibility. And as I got out to really start to meet with some of the shareholders, I think we went to five or six different cities over the last three or four months.

And what became readily apparent to me is that there is a real thirst and really an inclination for groups to want to come together in nontraditional ways to sort through and begin to solve some of these more systemic issues that are really plaguing our industry. To really look at ways of trying to address whole health and wellness, and not just continue to treat the symptoms of what we have. And obviously that’s being driven by some of the reimbursement challenges, some of the inherent barriers to continuing to practice the way we have historically practiced. And I think that timing is actually favorable for the shareholders in this room to begin to think about ways to come together and collaborate in places that maybe we haven’t done historically. So I think the timing is really now. And I think the industry at large is eager and anxious to engage.

WOLDT: Steve, maybe you want to amplify a little bit. NACDS has made some good progress in Washington on PBM reform and other important issues.

ANDERSON: Yes, we’ll get into some of these in greater detail, but thanks to all of our great members, we’ve made some really significant progress in our existential battle with the pharmacy benefit managers. We’ve made great progress because the unanimous Supreme Court decision in 2020 that we got in the Rutledge decision [Rutledge, Attorney General of Arkansas v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association] allowed us to continue what we were doing in the states to pass PBM reform laws.

In addition, we have made unbelievably great progress in Congress. I remember we had a board fly-in probably five or six years ago. We were trying to explain to a member of the Democratic leadership in the House of Representatives what a PBM was. And then once we went on to DIR [direct and indirect remuneration], it became even more complicated. But we made unbelievably great progress. While we now have tremendous momentum behind PBM reform in the U.S. Congress, we cannot assume that will translate into enactment of a law. Think back to 2019, when many signs were pointing toward executive branch action on DIR fees in a Medicare rule. Just as I caution our members now, I was the one of the people who said in 2019, “We haven’t gotten a DIR rule yet.” And it was killed at the White House. But we have to just keep doing what we’re doing, keep achieving progress, and keep the goal in sight. Pharmacy can’t get complacent.

Along with what Mike said about collaboration on systemic health and wellness issues, author and leadership guru Jim Collins comes to our meetings quite often. He’s been coming for about the last 25 years, and some of you have heard him speak. When he last spoke in 2017, he said NACDS was one of the best-run associations representing the most important industries in the country. He said one of the strengths of great organizations is they protect the core but stimulate progress. And that’s what we’re doing with our NACDS 2023 initiatives.

We’re going to have an exciting, unprecedented announcement tomorrow where we’re partnering with the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association and the Food Is Medicine Institute at Tufts University. There are a lot of exciting things going on. We’ll talk about what the future of pharmacy and broader health and wellness are going to look like. That’s going to play a really lead role, because — to use a Jim Collins term — we have all these “level-five leaders” on our board, with Dain and Mike and Karen, who are with us today, and with our stellar staff, we’re making good progress on these issues that we’ve been working on for a long time.

So, to answer your question, Jeff, we continue to advance PBM reform even as we focus on this innovative health and wellness platform. As Jim Collins said, protect the core and stimulate progress.

We have this heat map that we update daily with all the different PBM bills that are going through the states. The issues get really complicated when you’re doing PBM reform. There are all kinds of different iterations, and we’re working to make sure that they comply with the PBM principles that our board established for us to achieve. We’re making good progress in the near term, and in the long term, I think the future is bright.

WOLDT: Publix played a key part in passing an important PBM bill in Florida. Dain, maybe you could talk a little bit about that initiative.

RUSK: Sure, and just to add onto what Steve just said, it’s probably the first time in a long time that we’ve seen actual bipartisan support both at the state and federal level. I mean they really are all in. We’re seeing it right now at the federal level, where many of these things are making it through these different sessions almost unanimously, which is what we saw in Florida.

Our approach was to really just try and amplify the approach NACDS had already set in motion when we were interacting with the state of Florida. We learned from states like West Virginia that were very, very successful and did a great job on really getting all the key points addressed in their reform bill. And it wasn’t just Publix. It was a huge effort from NACDS, and Walgreens was actively involved in it as well.

But the thing that we have to continue to look at is how do we get to some sort of standardized practice in terms of reimbursement. Because the bottom line is if we can’t protect the reimbursement part, all these other efforts that we’re trying to expand upon really start to become a challenge. I think that our biggest problem at this moment — with all the legislation that’s out there — is not having a rate floor so that there’s fair and equitable reimbursement for everyone so we continue to have improved patient access for all patients, with more pharmacies and pharmacists providing care versus decreased care due to pharmacies having to close their doors.

Steve Anderson, NACDS

ANDERSON: Publix and Walgreens did a great job, as demonstrated by Dain and one of his pharmacists standing next to the governor when he signed the bill into law. I think one of the game changers, too, is what’s going on at the Federal Trade Commission. They launched an inquiry into the PBM industry in June of 2022. Several weeks ago, they warned the PBMs that just because the FTC said something in the past doesn’t mean it’s going to be current policy moving forward, because the industry has changed, and the nature of the PBM activity has changed aggressively since the original regulations came out.

We also have a House of Representatives Oversight and Accountability Committee that has launched its own investigation of the PBM industry on a bipartisan basis. The FTC inquiry will be interesting. It takes a while, because they’re ordering the production of all kinds of records from the PBMs. It takes a lot of time to put all that together. They’re taking a multipronged approach to this whole issue, and there’s a lot going on.

WOLDT: How much pressure do retailers — not just Rite Aid — feel? Steve was saying that it may take a decade to get a bill passed. How long do pharmacies have?

STANIFORTH: Like Steve just said, while you want all the rules and regulations to change, you can wait or find ways to expand what we’re doing outside of that.

Now is there a way we can keep moving forward and do what we need to do without having to wait a really long time on other things? I think there’s still a long way to go for all of us. But we should feel pressure, because to Dain’s point, as reimbursement rates continue to decline, things like generic inflation continue to grow, and the margin just keeps getting smaller and smaller and smaller. And dispensing medications isn’t where we’re going to make money. It’s in clinical services. And so if we can’t keep the COVID-related clinical things open and moving forward, it’s going to impact access, outcomes, care, all of that.

TOMIC: I couldn’t agree more with what Karen’s saying. Our two challenges, and opportunities, are exactly that: reimbursement and regulation. How do we remove all those transactional pieces out of our stores? We have to figure out how to do those things cheaper, quicker and not necessarily within our community-based pharmacies, so that our pharmacists can practice with the full scope of their license. But the key there is also being able to get reimbursed for those services. And so that’s our challenge right now.

WOLDT: Walgreens is working pretty aggressively to take scripts out of the store with central fill, aren’t you?

TOMIC: Yes, we have a micro-fulfillment model deployed, where our goal is to take 40% to 50% of our prescriptions out of the pharmacy, to use systems off site, and then to be able to take that time and focus on our patients in a different way.

STANIFORTH: That’s exactly what we’re doing, too.

Jason Ausili, EnlivenHealth

AUSILI: I think that’s an important theme. How do we make our pharmacies more efficient? Technology and automation take tasks out of the pharmacy and save time that can be reinvested in clinical services. The pandemic has really shined an important light on the value that pharmacists bring to the table. Accessibility is second to none: 90% of the population lives within five miles of a pharmacy. But in the face of an increased PCP (primary care provider) shortage, we also have a higher-touch model with pharmacies. So, I think that makes us ideally positioned for public health needs, but also social determinants of health (SDOH), and the list goes on and on. I love to hear that you’re focused on taking work out so that pharmacists can spend more time with their patients.

HUSEBY: There was a point that was made earlier about Jim Collins, protecting the core while still advancing. Someone in this industry, one of the leaders, used to talk about good disruption and bad disruption. And the PBM reimbursement basically is going below cost. It’s an example that nonetheless America is trying to control health care costs. This is one way; it’s working its way through the system. But these things like central fill, that several players at the table have in changing the operating model, is probably an example of good disruption.

STANIFORTH: I was going to say that it’s not just the operating model itself, it’s really the role of the pharmacist that will have to change dramatically in the next two years. Not their knowledge or what they know they can do, but just the role they play in community pharmacy will have to change.

WOLDT: We will dive into that a little further in a moment. Did you want to comment, Mike?

WYSONG: Yes, this is what I was talking about, that pivotal moment. It’s all of these things happening at the same moment in time. So if the reimbursement is declining, if you have generic deflation, and you have growth now in all these high-cost branded specialty drugs, and you have these wholesaler models that are deflating at the time you need to offset the reimbursement challenges and sourcing issues, then, to your point, you’re going to have to find ways to take costs out of the system, when the system is likely going to reward a high-touch model in the future, because you’re going to end up with an expansion of patient-based services.

So how then do you begin to make that pivot and transition in the most humane way for the customers that you’re not serving today but the ones that you hope to service in the future, and begin to do those services when you’re not being reimbursed for them today? And that really is the nuance of all of this. So as I’ve been out talking to all these people, this problem exists across the entire industry regardless of which stakeholder you are, whether you’re a wholesaler, whether you’re a manufacturer, whether you’re a consumer product group, or a provider or retailer. It is a pivotal moment in time.

And my sense of this is that with the reimbursement challenges, things that are happening at the state level now bubbling up to the federal, that’s all going to happen at some point in time. It’s probably not going to happen tomorrow. So the question then really is what do we do as an industry to begin to move past the current infrastructure? I’m a car guy. This is like how do you move to electric vehicles when the industry is completely set up today to support the infrastructure of the existing industry? How do you successfully make that transition? And my sense of it is that all of this is going to play to the strengths of the group that’s sitting here today: a high-touch model that rewards those people who really preside over the patient-provider relationship in a better way moving forward.

ANDERSON: Along those lines, I believe that our members need to play a role in the future. There was a recent New York Times Magazine article with a headline that said we’re suddenly in the golden age of medicine. It talked about using different new technologies to treat illnesses from heart disease to Alzheimer’s and how we can play a role in that. I think we are entering a golden age of medicine, but we’ve got to collaborate with our members as they are moving in that direction. With this agreement we’re going to announce tomorrow there’s a key role for that. I think it will be a really, really exciting time, and with machine learning, all of this progress is going to be even more intriguing.

WOLDT: As you said, some of these things are going to take some time, but we’re facing some significant changes in January.

HARDING: Yes, I brought some data I thought might enrich the conversation. Some of these you are probably very familiar with. But over the last four quarters, DIR has represented, across the industry, a cost equal to 3.6% of total Rx pharmacy sales. It’s a significant number, and it’s been increasing year over year over year.

At the same time, reimbursement rates in the first half of 2023 are down pretty significantly from 2022. What’s going to happen is that, in January, it’s going to present a cash flow problem for pharmacies, because DIR fees will all be taken out immediately at the point of sale. And the challenge is it’s actually creating less transparency for pharmacies because the DIR fees and the reimbursement rate are getting combined together in these agreements. It’s going to be very difficult to know if you’re getting paid what you should be getting paid.

RUSK: It’s going to affect the small pharmacy. The independents are going to struggle that first quarter.

HARDING: Yes. The first six months could be very difficult.

RUSK: You’re going to see a lot of independents have to close their doors because they’re going to have a cash-flow problem.

STANIFORTH: There’s also back-pay, coming out the first six months of the year.

RUSK: Right. So the larger ones can survive. But that stat alone is going to create more downward pressure, and pharmacies will have to close their doors.

HARDING: It absolutely will. And I think it’s going to be really significant, as pharmacies move forward, that we’re seeing people move away from effective-rate contracting. In order to support all the legislative activity, it’s going to be important to have really simple, clear data to prove your case with a legislator so that you can support making these things happen. So we’re seeing people moving away from effective rates.

WOLDT: I’d like to hear from Jenni and Nancy. Obviously the independents will feel the pressure first. What do you expect?

LYONS: Yes, I was just going to say we are expecting a lot of pressure on the independents. Health Mart Atlas — McKesson’s Pharmacy Services Administrative Organization (PSAO) — has been engaged early with its pharmacy customers to educate them about the cash flow impacts associated with the change in how DIRs are collected and to encourage them to put money aside to prepare. Additionally, Health Mart Atlas offered a solution called DIR Assist to allow pharmacy customers to escrow a portion of their reimbursement for disbursement to the PBMs in 2024. We’re hopeful that these efforts were enough. We’re concerned that some may not see the issue coming or be as prepared as they need to be and result in greater ramifications. It’s so important to help bring awareness and help independents pharmacies prepare so they can continue to operate, as they play such an important part in making sure communities have care access.

Jennifer Zilka, Good Neighbor Pharmacy

ZILKA: I would agree with that, and in education, and encouraging them to get lines of credit from their existing lenders. It’s big. Another thing that we can really focus on is balancing the train coming down the track by advocating. Because we will advocate and Health Mart will advocate. And you’re all advocating. There’s something really meaningful about a constituent in those states and those jurisdictions: You can go into the pharmacies to really, truly understand the impact that they’re having on their patients.

So I think that’s definitely something that we, at our recent trade shows, really were focused on. We will help tell your stories, and so many people will continue to do so with our industry partners. But you also need to tell your story, because there’s so much grassroots energy, including in the states. And if they can continue to push that forward, I think it will be really meaningful. But yes, it’s going to be a challenging first quarter of 2024.

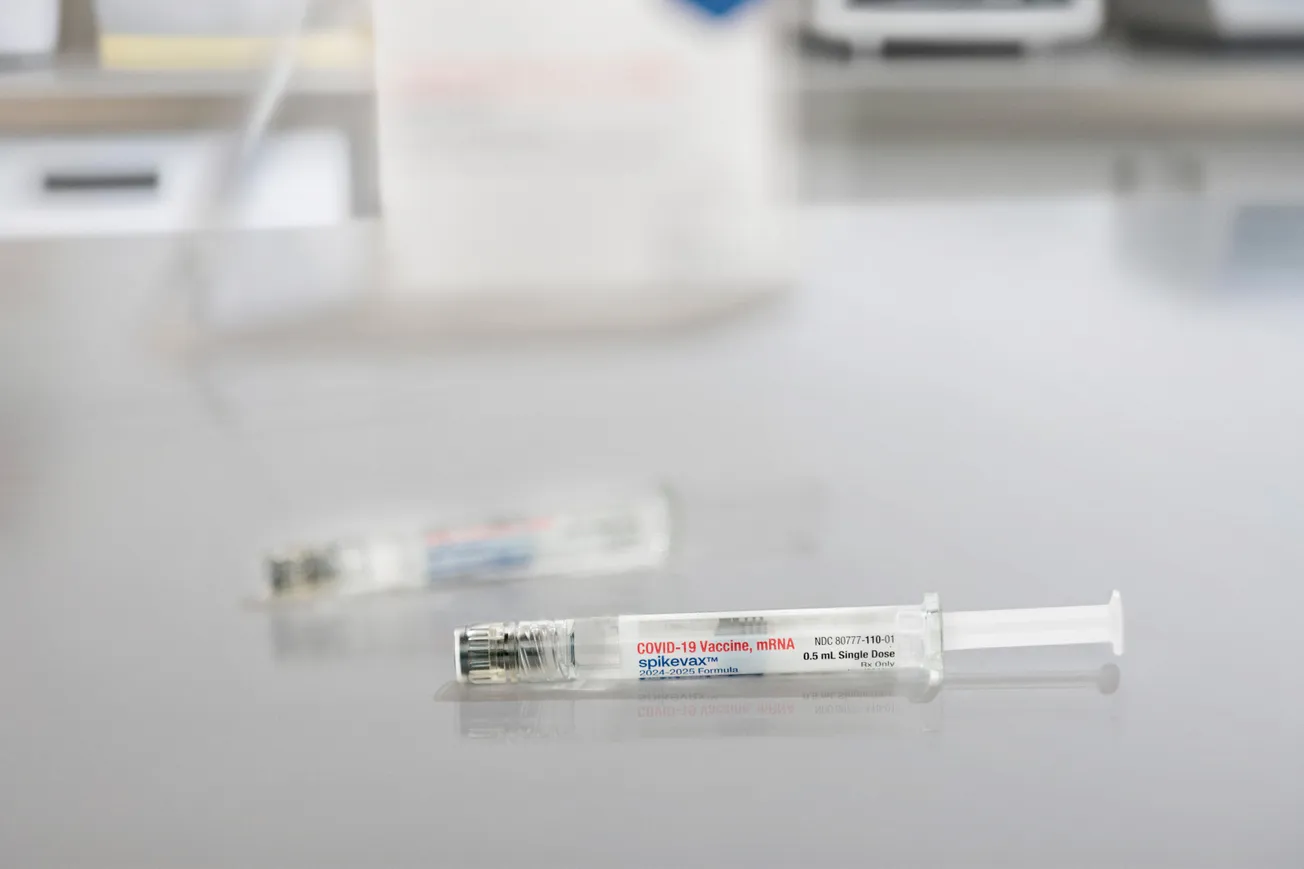

LYONS: As we all continue to focus our efforts in the Equitable community access to pharmacy services legislation and the country moves on from the pandemic, my hope is government agencies don’t have short memories. Just thinking about all of the public goodwill that the profession earned during COVID — we were all so proud of the work our teams did to stand up and lead in a public health crisis. The evidence is clear. Pharmacy led the way in meeting the needs of the country. We need to keep our collective voice strong to be sure that the legislative changes that are critical to patient care are not doubted and when the bills come for a vote, every member of the House of Representatives and the Senate offer a resounding yes.

STANIFORTH: You are so right. That is a very real issue — short memories. We saved the world just a couple of years ago, a year ago.

LYONS: And for the last 30 years.

HARDING: It was also financially beneficial to pharmacies, because between 5% and 7% of their pharmacy receivables were coming from COVID vaccines — which turned out to be a profitable business.

WOLDT: Two years of substantial profit.

HARDING: That’s now down to nothing. It’s very, very minimal at this point, so that’s another profit pressure.

STANIFORTH: I will say this though, the PBMs themselves are actually struggling with the whole DIR rate issue. Even they don’t have it all straight when you actually have conversations with them, which is fascinating to me. Because as they add the DIR into the rate, even they are not 100% sure of what they’re doing.

SULLIVAN: Yes. When you talk about what do we do during this transitional period, everything we’re trying to do is to take costs out of the retail pharmacy, with different solutions that reduce the steps or open up that capacity for more clinical functions within the retail space. The benefit will be the reduced cost initially. Until the reimbursement comes in for the additional clinical, all we can do is help you open up that space, and then those laws have to move it along. But I see that as the transition. Can we reduce those costs so that the pain is less until that transition happens?

WOLDT: Sean, as a manufacturer, how do you view this development?

SPEARS: I always enjoy this forum because I learn more about what’s going on in the industry. As Karen pointed out, pharmacy is changing. We just launched an Alzheimer’s drug, leqembi. Every step we make is breaking new ground. As a manufacturer, I know Eisai has worked with retailers and wholesalers on different patient programs that focus on adherence. We may consider similar programs for leqembi in the future.

HUSEBY: Just one thing: Steve mentioned 10 years in terms of legislation. Take 3.5%, as a round number, different year by year, company by company. Play it out over 10 years and you’re talking about, for a given drug, maybe reimbursement reduced by 50%. So you’ve got to just chase the efficiency so fast in order to be able to stay ahead of it.

HARDING: Couple that with brand-effective rates were AWP-19.20% in 2022, and in 2023 year to date have fallen to AWP-20.17%. That’s a whole other percent right off of the reimbursement rate. Brand extended days supply claims are now averaging 24.14%, and effectively a loss for all pharmacies. In 2022 they averaged AWP-21.87%. It’s 2.27 points down in 90 days for brands.

STANIFORTH: No question about that. The numbers are big.

RUSK: And the problem is the system is set up such a way that the PBMs are negotiating higher-cost branded drugs on their formularies — because that’s where they’re getting their rebate dollars. And those rebates, it’s highly unlikely they’re passing them back 100% to the plan sponsor to reduce costs. So in the end, we’re just perpetuating the problem of driving up higher-cost drugs that pushes the financial burden down to the patients, in the form of higher co-insurance and deductibles. And then the pharmacy is struggling because they are getting reimbursed below cost; therefore you’re left in a position where you don’t want to participate in certain networks, once again reducing patient access to care. That’s the unfortunate truth.

STANIFORTH: And that’s a terrible conversation to have as a pharmacy team. Like, “Should we stop dispensing GLP2s?” And then you think about how crazy that is from the clinical pharmacist’s perspective. Because the truth is that person who genuinely needs that is also on 10 other medications, because they’re diabetic or they have other health conditions. But, I mean, just to your point about AWP, the GLP2 craziness that’s been going on the last few months has definitely impacted all of us.

ROTSART: And Mike, you said earlier it’s a pivotal point in time. I look at what you’re doing now, and what I’ve seen in the business over the years — it’s really great to see everybody pulling together, recognizing we’re in kind of a struggle to survive. Everybody is finally in the same boat, pulling in the right direction. So the PBMs at least brought us together that way.

My company works with major manufacturers to find funds to support patients that are on certain meds, and then brings this together with retailers such as Walgreens and Rite Aid, actually everybody here, to provide this access to the patients. And so there is money out there, and there is actually support from the industry. Everybody needs pharmacy to stay alive, and I think groups like this are going to make it happen. But the work that NACDS is doing, leading this PBM fight, I think we’re going to get through it. For me, it just feels good to see everybody pulling together to do the right thing.

WOLDT: We talked about support growing for pharmacy, and how the industry is making progress on Capitol Hill. Let me ask the group: Are patients being harnessed to play a part in all this, or are they unaware of the challenges that pharmacies now face?

STANIFORTH: My perspective is that the patient population loves their pharmacy and really appreciated everything we did during COVID. But I don’t think that they see anything more than that. I don’t think they really would be advocating for us and fighting to give vaccines, like we were during COVID, and now we’ve got states where we can’t even give vaccines to children. Even RSV, you can’t give in New York State at the moment.

Dain Rusk, Publix

RUSK: I think patients are dealing with their own financial issues, so they don’t have time to worry about the pharmacy’s problems. Cost-sharing for patients is at an all-time high. Plan designs have changed in such a way that you’ve got to hit high deductibles before your lower cost-sharing in the form of co-pays even kicks in. With those things alone, I think the patients are trying to fight their own battle, which is, “I can’t afford my medication.” The bottom line is pharmacists are out there working really hard for their patients to get them access to their medications and provide clinical services and are not getting paid for it. That’s the bigger problem from my perspective.

ANDERSON: On a lot of our policy work, we use a polling firm called Morning Consult. Pharmacies always score really, really well. And when we go into the field with polls, we gain insights about how best to summarize our issues. As you may have seen, along with Michael Hogue of APHA (American Pharmacists Association) and Doug Hoey at NCPA (National Community Pharmacists Association), NACDS sent a letter to the Food and Drug Administration about the DSCSA (Drug Supply Chain Security Act) — urging for a delay in full enforcement of that law to help prevent unintended consequences like drug shortages. And we just received results of the survey that Morning Consult conducted and that NACDS commissioned on this topic. When you talk about drug shortages, that’s what gets their attention. When you focus on those kinds of issues that hit people’s bottom line, or that affect their ability to take care of a sick kid, that gets their attention. We need to make our case in terms that resonate with people.

TOMIC: I just want to make a comment. I think we still have some work and continued focus to do on changing the perception of the profession, just in general, with patients and with our own pharmacists. Our profession has gone through a lot over the last two years. They’ve been on the front lines and literally, as Karen mentioned, saved the country. And so we have some rebuilding to do with that as well, working with APHA and other organizations on how do we come together to really fight for the profession. If patients then see us in a different light, they will come to us for the clinical services that we want to be able to do. But today, if you tell a patient they can come in and we can test for HIV, we can possibly give them a prep, they don’t necessarily look at pharmacy as the place to go to be able to close those care gaps. And so I think really changing that narrative of what pharmacy can do, both among our pharmacists themselves and their patients, is critical.

Sean Spears, Eisai

SPEARS: I have a relative who is going through dementia, and I suggested an MTM (Medication Therapy Management) visit to the pharmacist. The visit was successful, and my relative loved it. My family did not know about MTM. This is one successful example that pharmacists can do great things for patients. We need to do a better job of educating the public about these programs.

SULLIVAN: I did the exact same thing with one of my relatives who has 20-plus medications. I said, “You know, you could probably hone that down, and there’s actually a way to do that.” And I explained MTM to her, and she was going in for that. But she had no idea, and I don’t think a lot of people outside of our industry do know that.

LYONS: It’s all about that, though, because what does MTM mean? I don’t even think some pharmacists can accurately define it. But if we can get some consumer education about the value of what they get, the benefits of just talking to your pharmacist. APHA has done a great job of that in the past, especially during American Pharmacist Month.

But it needs to be more than just American Pharmacist Month. The education needs to be year-round. I’m again thinking about the critical role that independent pharmacies play and the risks we talked about before regarding DIR uncertainty and potential cash flow impacts to their businesses. Patients who do have strong relationships with our independent pharmacists would be very surprised. If we can educate consumers ahead of time, perhaps that will stimulate some patient-driven constituent-based activity, which can only make our message stronger.

AUSILI: We can’t expect patients to understand PBM reform and the struggles that pharmacies go through on the reimbursement side. But there is one way we can help translate this to patients. We’re coming up on Medicare Open Enrollment, and helping patients find the plan that’s going to work best for them and be OK for the pharmacy is the overall goal. This is a process that many pharmacies haven’t thought about before, but you want your patients to talk to their pharmacist about the plan that might be best for them.

Thanks to Steve and his team, along with APhA, NCPA and ASHP, the 11th amendment of the PREP Act has passed, and pharmacists’ pandemic-related privileges have been extended. As shown by a recent Morning Consult poll, a bipartisan majority of patients wanted these services to be available beyond the pandemic. And I think that this awareness is much, much more empowering. As a result of growing patient engagement, we launched a website or initiative called Ask Your Pharmacist to drive more awareness on the patient side. But there are three parts: Patient awareness of the services they can expect to get at their pharmacy beyond filling scripts is also meant to drive a healthy dialogue between a patient and their pharmacist. Also it intends to motivate and inspire pharmacists to practice at the top of their license and embrace the growing provider status movement. Finally, this initiative gives us an advocacy arm to influence positive change on the legislative front. So, if anybody wants to partner with us, we’d love to have you join the journey as well.

Karen Staniforth, Rite Aid

STANIFORTH: I wasn’t at the meeting, but I heard back from my team that was at the HHS meeting with Secretary [Xavier] Becerra in July, that there was some dialogue with him about how many times a year a pharmacy communicates or engages with their customers on average, and that really resonated with him. And then, as you know, he was out visiting one of our stores. It was actually really awesome. The pharmacist from that store engaged with him about a mental health story that she had. And I think even that kind of awareness, as he goes around to promote the Inflation Reduction Act and the Medicare drug benefits impact, I think just having him be more public about it was important progress in the last few weeks.

ANDERSON: Yes, Karen’s referring to a meeting that we had at the White House on the Inflation Reduction Act. Secretary Becerra basically said pharmacy is on the first team. You were on the bench for a while, but you’re in the starting lineup, and Secretary Becerra really has a passion for it. He was in Oregon, right?

STANIFORTH: Yes.

ANDERSON: So he understands. Secretary [Alex] Azar said the same thing during the Trump administration. The NACDS board of directors met with him during his third week on the job, and he said, “I want to put pharmacy at the center of health care.” And he did that, for the most part.

WYSONG: There’s a commonality in everything that’s being said here as I’m listening to this. Every time I hear a comment, it comes down to two things, and that is the capacity and capabilities of the people that are in this room. And as I said before, when you go around, there is a growing acknowledgment that pharmacy has the capacity, and the infrastructures already exist. You saw that in the pandemic. And the capabilities have not been fully harnessed or tapped. So maybe one of the takeaways for us is we probably need to do a better job of educating patients and the public on the capabilities of that infrastructure, because it’s there.

RUSK: It’s interesting. The pandemic provided a real-life use case for two years where pharmacists were thrust into the limelight. And then as policies were about to expire, you had a bunch of politicians going “Oh my God, what are we supposed to do?” I mean common sense would say continue. But we let the process get in the way of progress far too often, unfortunately.

ANDERSON: It was a two-year fight.

RUSK: And it was crazy.

WYSONG: But to your point, there is a case scenario proving that out.

RUSK: Exactly.

WYSONG: And there is also growing awareness when you go into the Congress or you go into the Senate. There is a fear that if they have fewer pharmacies, that’s not a good thing. Not when you look at the sheer number of people that are coming into the system and the shortage of health care providers that you’re likely going to experience in the not-too-distant future. So I take it full circle, which is I don’t think anybody is better positioned to address all of that than this group. So how do we do that? How do we make that successful pivot, whether it’s through efficiencies in automation, whether it’s from manufacturer support, better programs at the patient level, an expansion of services out in some of the pharmacies that we have, how do we usher that in, I say in the most humane way, because to your point, it doesn’t look very humane, does it?

HARDING: No, it doesn’t. Patients are feeling the pain. Inflation has been at a record high, and it’s a challenge for them to pay for everything that they need to pay for. In 2022, 38% of all prescriptions filled were 100% paid for by the patient — with no money coming from any other payer — because of these high-deductible plan designs. You guys know patients are all searching for discounts, and they’re using these discount cards. The discount card generic-effective rate is the lowest at AWP minus 95.39%, and then you have to pay a fee for that. Even Medicare patients are using these discount cards, because they can get their medicines cheaper. They’re searching for every possible way to be able to afford their medicine. This whole situation is counterintuitive to value-based care.

WOLDT: Jenni, do you see the factors that Lari’s been talking about affecting patient behavior? I mean do they come in less frequently? Do they not refill the medication they’re supposed to?

ZILKA: I think we’re absolutely searching for health, in the way of cost, access, etc. I feel like we absolutely must educate patients and consumers. I think that’s something we need to come together to do.

But I’m also asking myself if we need to educate manufacturers around the economics of the pharmacy, too. I don’t know if there’s an opportunity for us in the group, independents of course being kind of on an island. You all probably have great relationships with manufacturers in the chain environment.

But I wonder if there’s also an opportunity for us to educate not only consumers and the general public around the value of pharmacy, but also potentially manufacturers. If I’m a manufacturer and I’ve spent all this money on this product, that pharmacist who’s dispensing that product is the face of that product. And if the business is in the red and it’s under water, they’re probably not going to be as much of an advocate as perhaps they were hoping they would be. And it’s because the system is broken, and the dollars aren’t going to the pharmacy or the patient.

RUSK: And the manufacturer probably would say that they assume that the rebates they are providing are being distributed equitably. They’re actually leading to more profit on the PBM side.

ROTSART: I can tell you that’s basically what our company does. That’s what we do. And so we work with every major manufacturer.

STANIFORTH: That’s the workaround.

Jim Rotsart, MedAdvisor Solutions

ROTSART: Right now we help bring available funds into the system. So we help everybody, including independents, support their patients to stay on their medication. We provide education to the patients that’s approved by the manufacturer. Manufacturers understand that you have limitations. It’s another way that they can support patients. And they’re fairly successful. It’s happening across every major manufacturer, at least 60 to 70 products right now, so they’re learning that they have to support patients, and they have to do it outside the PBMs.

STANIFORTH: Right. And I think that’s the workaround I mentioned previously. You’ve got to find ways to benefit. We have a bunch of contracts for managing patient adherence for some high-cost drugs. You’ve got to go directly to health plans to look at these services for lower cost of care alternatives. In Michigan we have point-of-care testing, and nobody’s paying for point-of-care testing, and no patients want to pay cash $35 to $50 to do a flu or strep test. But these are all the ways that we have to be working around without getting the reimbursement another way.

WYSONG: It is, but there are four or five answers to that. We’ve had a high degree of success working with manufacturers to subsidize or improve some of the economic equation.

I can tell you, we’ve met with many, many manufacturers, and that is a statement of fact. Many of them don’t really understand.

SPEARS: They need a pharmacy champion.

WYSONG: Again, for the same reason your patients don’t.

SPEARS: Yes.

WYSONG: It’s such a dynamic that I tell people, pharmacy is the greatest industry ever, because it changes tomorrow, and there are 800 things that are all happening at the same exact time. Can you imagine anybody understanding? It’s hard for me to understand.

RUSK: When we were in Florida trying to talk to politicians, the very first concept. They said wait a minute, the manufacturer issues a rebate — why don’t we just drop the price of the drug from the beginning? Why don’t we just put drugs out there at their real price so that patients aren’t paying these high, inflated deductibles. You try to explain to someone on the outside looking in, and they’re going, “Wait a minute, this makes absolutely no sense.” It makes no sense that you’re going to mark the drug up really high and turn around and give a rebate of dollars to the PBMs who are going to go distribute them however they see fit. And then you’re going to charge the patient the deductible they have to hit first. They’re sitting there going, “Why don’t you just tell the manufacturer to drop the price?” That is one reason why it takes 10 years. It’s so hard to explain this to policy makers, manufacturers, everyone involved.

WYSONG: Look at the progress that’s been made. Again, go back to your seven- to 10-year example. That sounds like a long time, but in context, when we go down to Congress how much more educated are the lawmakers today than they were four or five years ago?

STANIFORTH: They are; I agree.

WYSONG: So again, I think it’s a combination of all these things. It’s figuring out those four or five things that are going to allow that pivot to take place to mitigate all the things we’re talking about. And then begin to move forward here. And to tell the story, because if you don’t tell the story, forget it.

WOLDT: I think you have to. The other day, [CVS Health CEO] Karen Lynch was saying that PBMs are the only entity working for lower drug prices. If you’re a member of Congress that sounds like a pretty good argument.

ROTSART: So how do we as a group change the dialogue? It’s going to have to come from here. The dialogue has to change. The current PBM model isn’t set up to benefit patients. So you were talking about grassroots a little bit. Is there a way to get to the grassroots? I mean, there’s a drug store in every congressional district.

ROTSART: So you had the success in Florida. How do we get your success story to every other state?

ROTSART: So is someone looking at that and saying who’s the next guy that we have to go after for the next state? Who’s the next politician?

HUSEBY: Steve can speak to it better, but I think we take a look at what are the most important states where we can have the biggest impact. That’s kind of where we try to focus our efforts.

ANDERSON: And we prioritize the states with our policy.

Brian Sullivan, KNAPP

SULLIVAN: So if this is a pivot point, you’ve got four or five different key issues that have to happen, PBMs are obviously a work in progress, but you can’t say that NACDS isn’t on that every day, all day. I see it every day coming out of here. So that’s in process. The automation teams and other teams that are trying to pull process costs out of the pharmacy are trying to reduce those, because that’s in process. We see that the future is going to be pharmacists working at the top of their license and getting more clinical value. I guess what I don’t see, and I’m sure it’s happening, is how about those laws that are going to change the reimbursement, because that’s a big part of the puzzle. Are we seeing progress there?

AUSILI: There are two landmark bills coming through Congress right now. The first is the ECAPS (Equitable Community Access to Pharmacist Services) Act, which just had a Senate companion bill come forth in July and would rewrite the Social Security Act to recognize pharmacists as providers under CMS. This is really important to the Medicare population, limited to pandemic-related services, but still a landmark bill. And then there’s another one, Pharmacy and Medically Underserved Areas Enhancement Act, which focuses on medically underserved and rural areas and would amend the Social SecurityAct to recognize pharmacists as providers so that they can provide critical services to people who might not have any other access to care. So those need to pass. How long does it take? I hope it doesn’t take 10 more years. But hopefully in the wake of the pandemic, these bills have energy behind them that they didn’t have before. Unfortunately Medicare only looks at us as providers for vaccines and tests. And even if you’re on the DME (durable medical equipment) billing side, that’s not going to help us build meaningful clinical revenue.

LYONS: When CMS recognizes a provider other payers usually follow along, so that’s why it’s so important, too, even though we’d prefer something more expansive, we want to stay focused on what is an achievable first step.

AUSILI: Right.

LYONS: We know that the language in those bills is limited, but if we can get them passed, we will finally achieve that crucial step towards elevating the profession of pharmacy. Once we’re there as a provider, we will be able to keep the conversations going about all the profession can do.

AUSILI: Our partners at NASPA (National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations) and the pharmacy association executives across every state in the country have been really busy. They released a report in 2022 highlighting that 178 bills were introduced last year that were either provider-status-related, scope-of-practice-related or public-health-service-related. 44 of them across 26 states passed and were signed into law. In 2023 alone, we already have 38 bills signed, and 12 more that passed both chambers. So, there’s a lot of movement, but without federal recognition and backing, just like you said, Nancy, commercial payers are not able to fall in line behind CMS. So you’re left with, let’s see what we can do with Medicaid and what kind of services they will pay for, which is a great starting place.

LYONS: But Medicaid payment has been around for a while for pharmacists. For example, in Indiana, we’ve had the coverage for smoking cessation for a long time. The billing processes are difficult, and the service is underutilized.

AUSILI: Yes.

LYONS: For pharmacists, there are too many barriers to getting the claims through, and once the claims are submitted, to getting them paid. We have to get rid of the billing barriers for the providers to provide the care.

AUSILI: Absolutely.

LYONS: And for the dollars to come in for the services they provided.

HUSEBY: But I don’t think pharmacy chains are waiting on the legislation. They’ll advocate for it. But the investments going into buying providers is building vertically integrated care. All that’s under way, and we’re seeing that happen. And I think there’ll be a question, once you can expand the scope of practice for pharmacists, then what do you do with the providers that you’re paying an awful lot of money for, if the pharmacists can be doing the same thing, cheaper, better.

AUSILI: Paying at an eighty percent reimbursement rate.

HUSEBY: Yes.

WOLDT: Lisa, maybe you want to talk a little bit about the question of pharmacy operators’ involvement in primary care.

TOMIC: As you know, we have a relationship with VillageMD, and they’re in a couple hundred of our stores today, where we have collaborative-practice agreements to be able to make recommendations and change therapies and things of that nature for our patients. As for what happens afterwards, I think that that’s where we then set the bar even higher on what more can we do as a profession. But it’s an interesting point. So far, it’s been working out really great. Our pharmacists love it, especially our students that are coming in.

And that’s the other thing. And enrollment rates in pharmacy schools have dramatically dropped. So as you look at the pipeline, and as you look at where we’re going as a profession, we have to take that into consideration. So not to deviate on that, but, yes, our strategy is to move forward with these collaborative-type practice agreements and just be able to build and do more and more, and ultimately build those relationships with our pharmacists and our physicians. It’s still a work in progress. We’ve still got a long way to go, but that’s what we’re looking at.

SULLIVAN: So the opposite side of what you just described, we were up in Canada, and they’re putting in a clinic in a store on one side, and they’re changing out the pharmacy on the other side. And I was working with a young pharmacist who had gone up to Montreal from Toronto to work. She had interned there, to work in this pharmacy, because the connection of that clinic to the pharmacy made it so dynamic that it was extraordinarily attractive.

TOMIC: That’s exactly the same for our students, and we work with AACPA and faculty and deans to show the difference, how we’re truly clinical. And we don’t like to use the word clinical; Pharmacists are clinical by nature. But there are clinical practices within the community pharmacy setting, and having a partnership with VillageMD illustrates that I think, and it’s kind of front and center for our students and for the population.

HUSEBY: Canada has done some impressive things in expanding the scope of practice. So there are some really good ideas to look at for policies.

STANIFORTH: They have a national health system. And it’s easier, right, to manage through the system.

SULLIVAN: Yes, they’re having a lot of the same conversations that we’re having on this side of the border. But it’s a very different reality. They make money every time they dispense prescriptions. And so they say yes, the future is expanding clinical, but I’m not making money over there right now. It didn’t sound very attractive to them.

WOLDT: In Alberta, pharmacists have a lot of prescribing and testing authority, all sorts of things that would be the envy of pharmacists here in the U.S. That really should be a model.

STANIFORTH: All over the world pharmacists have some level of prescriptive authority, just not here.

RUSK: Jeff, it wasn’t necessarily on topic, but Lisa brought up a point that is really important, which is that we’re at an all-time high in terms of the number of pharmacy schools in the United States, and yet enrollment is down around 2017 numbers right now.

TOMIC: It’s down 40%.

RUSK: With the number of pharmacists that are coming out, it goes back to what Mike described where we have to invest in the technology so that we’re taking as much production as possible out of the stores because, if we don’t, we’re going to be in a crisis at some point, because people are opting out of going into pharmacy. I also think some of these schools really need to go back and take a look at what they’re charging for tuition. This is one of the reasons why people are opting out, saying I don’t want to spend all this money for six years and then be in a profession that may be floundering. So I think that’s something that’s very significant. I know the larger retailers are feeling that pain across the whole United States.

STANIFORTH: I think there are some other follow-on points to that. One is that even students coming out of college right now are not passing NAPLEX (North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination). And you see a record number of failures of NAPLEX. I think the statistics are actually incredible on how many fewer students are passing on their first try. And some are taking three to four tries to get through NAPLEX.

Lisa Tomic, Walgreens

TOMIC: To your point, the deans have said a number of schools have decreased their enrollment requirements. Back in early 2000 when I went to pharmacy school, it was tough. It’s not the case anymore. And then the other thing, and we’re working very closely with AACP (American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy) to really try to change that narrative of community pharmacy as well, that we are clinical, there is no difference in pharmacy. And so here are all the examples of things that we can do.

And then, especially with this new generation of pharmacists, there’s a lot of desire or need to have a very diverse type of workplace experience and workforce. So I may not want to be in front of a patient five days a week. So how do we leverage technology into other things that we can do so that they can work at home a couple days a week, and be able to still do pharmacy and have a couple of days in the store, or whatever they would like to do. So how do we get technology in place to be able to provide those different career-type opportunities so it entices our new generation of pharmacists to want to go into the profession?

We can differentiate that experience and then ultimately take care of patients in a different way. Because the patients are looking for a different experience, too. I want my care on my phone. If I can do it on a phone and do it quickly, that’s what I would love to be able to do. And I actually do that. I try to seek out ways to do that. So how do we leverage our pharmacists to be able to provide that care too, and they can do it in different practice environments and settings versus just behind the bench.

LYONS: It goes back to the pharmacist. We have to develop the future practitioners that are out there. I hear all of the things that you’re saying about mentoring them and showing them clinical practice. Clinical practice can happen anywhere with the right support. It’s up to us to show them the way that it can happen even in that community pharmacy, even in the chain pharmacy. I have both of those concepts competing in my brain right now. We’ve done it. We just have to continue empowering them to do it and setting our expectations. There was a time in our history when there was such a pharmacist shortage that salaries rose so quickly. And I think some of the people who got into the profession then were looking for the salary more than helping their communities.

We’re working on some projects right now to inspire and motivate diverse students early to consider pursuing pharmacy education. Mentors can help them see the value in not only using their connections to their communities but making sure they’re prepared and able to impact the population of people that they’ve grown up with.

WOLDT: Are you seeing a fall-off in people coming out of school who want to open their own pharmacies?

ZILKA: An interesting thing we’ve seen typically is that once they’re about five years into their career, they may have made a decision for the wrong reasons. Then they come out and say, “Now I’ve relieved some of my student debt, and I’m interested in the possibility of owning my own pharmacy and connecting with a community that’s underserved, etc.” So I would say that’s where we’ve seen fewer people coming out wanting to do it.

But, back to our earlier conversation around DIR in 2024, we are probably seeing those who were already thinking about getting out and are realizing that this might be the time to consider that. And we all work hard to match them up with either a junior partner or someone who’s interested in getting into that independent space, partnering with one of the schools that have more entrepreneurial programs. There aren’t many, but they are out there. And through those programs, we’re trying to teach them to understand the benefits of owning an independent pharmacy.

LYONS: Yeah, the only thing I would add is small businesses are hard to run, no matter the industry. But that’s the reality. McKesson has an RxOwnership group that is dedicated to working with those pharmacists who are considering opening a pharmacy but also connecting them to resources to help them stay in business. The team does a lot of education focused on helping them be businesspeople first. So many pharmacists graduate, spend a few years working for a chain pharmacy and believe they have learned everything they need. They believe now they are ready to do it better. And then the harsh reality comes in. Through mentorship and the work that the RxOwnership team does to help educate and remove barriers we can help them maintain the entrepreneurial spirit.

WOLDT: What kind of shape is the pharmaceutical supply chain in?

ANDERSON: In the recent poll that Morning Consult conducted for NACDS we found that 70% of those who experienced a medicine or health product shortage in the past year were supportive of delaying enforcement of “track and trace” of pharmaceutical products. They didn’t want to further risk shortages. That issue is on people’s minds.

HUSEBY: I was going to talk about drug choice for a moment. The number I’ve got in my head is something close to 250 generic drugs are short, and it’s been relatively stable, I think. But I’m just curious. A number of those drugs are cancer drugs, and it can be pretty severe for a family if they can’t get the drug that they need. And the pharmacies take a blow because you’re the face of that drug shortage, even though you didn’t have anything to do with it. It’s going to be an election year, so there’s going to be pressure.

STANIFORTH: There’s another piece of that. The FDA during COVID was not doing any regulation of any of the drugs that generic manufacturers oversee. So they shut down a bunch of factories and manufacturing plants. So that’s compounding and adding to this whole problem.

HARDING: Recalls are at an 18-year high.

HUSEBY: Yes, and they’re mostly going through India and China. And China has got its own issues, or trade challenges with us. So there’s a lot of pressure that’s coming on this part of the supply chain.

HARDING: And at the pharmacy level, there’s an operational effort to execute this in an environment where they’re already struggling.

ANDERSON: The point with these increased tensions we have with China particularly in the trade area, 90% of our active pharmaceutical ingredients come from China. And if they’re coming in from India, 80% of their active pharmaceutical ingredients, and they’ve already threatened to cut it off. So if that happens, we’re not going to be able to provide antibiotics to children. We’re not going to be able to get cancer drugs. The whole health care system collapses at that point.

WOLDT: Let me switch to another subject. Generative AI is here and, like most industries, it’s going to have a big impact on health care?

AUSILI: We’re at the tip of the iceberg. There’s a lot we don’t understand. I think we have to consistently think about what guardrails do we need to have in place. I do think there’s a couple of areas that stand out that are not necessarily no-brainers, but they lend themselves well to AI. One is with patient outreach, or communication with the patient. Think of a chatbot experience, where the engagement is more personalized and helps take workload out of pharmacies when technology can help answer more questions from a patient standpoint and even collect information from a patient.

Let’s say they’re coming in for a test-and-treat appointment, and you need to collect inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that this patient is actually a candidate. If you’re able to get that information in a meaningful way, and again, with the right guardrails, not thinking of all the things that AI can do, this could help drive workflow and make processes more efficient.

Next, and I don’t know if anybody’s doing this yet, but voice-to-text standardized documentation is another area where AI could potentially make the whole documentation experience more streamlined. Pharmacy has really evolved from a standardized documentation standpoint when it comes to clinical services. Not everybody is there yet, but as a profession we launched the Pharmacist eCarePlan several years ago, which was brought to life by clinically integrated networks. Now we are documenting in a standardized and codified way, which opens the door to interoperability, team-based care and value-based arrangements. So, I think there’s a way for AI to help with the documentation experience now that we have the foundation of standardized clinical documentation. I think there’s more we can do to make it more efficient.

ROTSART: Yes, Todd and I were talking about this a little bit earlier. We started to invest in some data science about two years ago, and we’re starting to use AI now. Not to engage patients or reach out to them, but to learn, to merely pour data into the system. How did they react, when did they react, what did they hear, how soon did they do what we wanted them to do? And these learnings are being infused into all the programs that we run through the pharmacies now. And I mentioned to him the results of the programs we’ve seen now are like five times more effective than they were even two years ago. It’s all because of machine learning.

We don’t see that there’s going to be a time probably in my lifetime when we’re going to let the machines actually talk, because they have to go through med rights. But you can learn behind the scenes, know exactly so many other things. Who’s listening, how are they listening, what are they listening to? And if you can employ them, then the programs get smarter and patients actually do behave much better than they were, because we are learning how to interact on their terms.

WOLDT: What about the pharmacy operators at the table. How do you look at generative AI and the way it might apply to your business?

WYSONG: I think it’s such a dynamic possibility. I think you said it best. We’re at the very beginning of what that is, but we’re definitely at a kicking-off point in technology. And I can go online and order a tube of toothpaste and have it show up at my front door faster than I can drive down the street and get it. What is the potential impact of AI on how we run and operate our businesses? I’m not sure. It’s kind of overwhelming to contemplate what that might be. I think we’re going to know a lot more in a short period of time. It’s an overwhelming proposition really at this particular moment in time.

ROTSART: That intersection of technology and AI is rapidly approaching within our realm. We can start using it now in more digestible, understandable pieces while still trying to get our head around the larger potential of it.

RUSK: The data, whether it’s pharmacy, or any other business, consumers want a more personalized experience. And that is what AI will allow us to do. And, as Jim said, with data we can tailor how we interact with them, how they want to be touched. It’s the whole concept of when they want it, how they want it and where they want it, that type of thing. But I also think, to what Mike was saying, I can envision where AI is just literally receiving a prescription electronically, processing it all the way through, and we then enable the pharmacist to be completely customer-facing, where technology is enabling us to move production out of traditional workflow. So I think there’s a multitude of ways of using it, but I do think all organizations are kind of stuck in this mode right now, which is what the guardrails are there to protect us from, because, left unchecked, AI is dangerous.

SULLIVAN: I was just going to say we’re using AI today at wholesaler level to pick medications, and a technology we use is that we have a common cloud knowledge of how to pick those medications. So if I pick this type of medication, this shape, this size in the past, my robot, if I install it next week over in your pharmacy, or in your wholesaling operation, it will immediately know how to pick that type of medication. So that works well at the wholesaler level. We have to lighten it up for the pharmacy, but in my mind, it’s going to happen, because it goes right along the lines of pulling mundane tasks out of the hands of technicians and they get done automatically.

Todd Huseby, Kearney

HUSEBY: To build on Brian and Dain’s comments, part of the workflow at pharmacy that drives, I think, everyone nuts is adjudication rejects or third-party rejects. And the number of ways technicians go about solving it, it’s just not a tightly managed workflow problem. And the more complicated drugs get, the harder it is, and the more at risk everything is. It’s the perfect problem for machine learning. It’s not generative AI exactly. But you’ve got tons of data on how these things have been solved. A machine can go look at how it should be done and eventually just automate it.

ROTSART: That’s right, totally.

HUSEBY: That’s just an area that strikes me as so ripe. It’s not generative AI. But it’s ripe for machine learning.

ROTSART: That’s right.

STANIFORTH: I think the other place that it has a use is in our clinical interactions, identifying who is the right person to talk to to get the desired outcome. There’s a ton of information as you build these models, that help you do that better than we do it today. So a pharmacist is interacting with a person who is going to be able to actually improve their outcome versus someone who will never engage with us. And so that’s another way that we’re using that machine learning AI.

WOLDT: It’s a very powerful tool, very powerful, but it’s not always correct. AI makes mistakes.

STANIFORTH: That’s why you need pharmacists.

WOLDT: Yes, exactly.

STANIFORTH: Amazon will never be able to replace the service that we provide directly to our patients and customers. Amazon cannot give you an immunization. So there’s always going to be a place, I believe, for a pharmacist to engage. People who talk about their mom doing a CMR with a pharmacist — and you both talked about that — that means that nothing will replace that human connection.

WYSONG: You can’t automate that.

HUSEBY: But I do think, the point that I was making, it does have a possibility, of being able to eventually ask the right questions and only the right questions in a better way, not just on a phone call or in the pharmacy counter experience.

STANIFORTH: Yes.

HUSEBY: And there are all sorts of things, I think, that it can do, but I don’t think it’s there yet. But I find Amazon interesting, because that’s one of the, I think, overlooked investments they’ve been making. But it does have some intriguing possibilities.

ANDERSON: With AI, machine learning, and innovations with the human genome and mRNA vaccines, we’re probably entering a golden age of biomedical research in terms of what we could do. I mean, look at what’s happening with these weight drugs and the impact that has on the rest of the system. It’s pretty amazing what’s happened. And it’s going at an exponential rate.

WYSONG: You will see more

of that, too.

ANDERSON: Yes, they’re on the cutting edge of this.

WOLDT: Let me raise a final topic — value-based care: That’s what we all say we want. Where are we, Mike Wysong, in terms of making it a reality?

WYSONG: We’re getting there. I think it’s commensurate with everything else. You’re not there; you’re on your way to getting there. I think the system is naturally going to take you there. And, like I said, I’m pragmatically optimistic about all of these issues, even in spite of our friend down here with all her terrible statistics. I am pragmatically optimistic that all of these things are going to find themselves on the other side of this. You can see it going there. Value-based care I think is a necessity. You’re going to end up there. You’re going to end up at the fee-for-value and movement away from fee-for-service. We’re just stuck in that.

I’ll tell you a stupid story. I work in the yard a lot, and all my tools are gas-powered tools. My wife goes, “Man, you need an electric weed whacker.” So I break my gas-powered weed whacker, and I go to Home Depot. I buy a battery-powered, way better than the gas-powered weed whacker. So all my tools now are electric. The same thing is going to happen here. All these backend issues that you have that are keeping us from moving from a fee-for-service to a fee-for-value model, they’re going to come in. There’s a growing awareness down in Washington that this is going to head in the direction that it needs to. I think you’re going to see that happen here in a pretty reasonable period of time.

RUSK: We have to have standardized metrics. It’d be like going to school and getting a report card at the very end of the semester, and you find out at that point that the teacher has raised it from a 90 to 100 today to get a grade of A. There has to be a standardized practice that you’re measuring against that everyone’s held accountable to and is transparent.

WYSONG: I can tell you this. I’ve benefited from my involvement in the association, at both the state and federal levels through the initiatives. The state teams are highly focused on all the things that we talk about to make sure that that is leveraged across other key areas to drive that at the federal level. You’re going to see that. You can see it here even recently. There is a growing sentiment that there’s great progress being made here in the movement to that, even though it seems like it’s been 10 years …

ANDERSON: And some big stakes.

WYSONG: Yes.

Lari Harding, Inmar

HARDING: I think Dain’s making a really good point. I think the clinical side of value-based care is ahead of the business model. We need to work together to make sure that it’s a winning model for pharmacies, but the business models have to mature. We’ve got to do some experimentation so that we don’t get caught up in having a PBM reform conversation 10 years from now when we can’t make money in value-based care.

WOLDT: Are there experiments involving other retailers?

TOMIC: Our partnership with VillageMD is all based on value-based care. Village’s whole model is based on that. And so how we integrate and how we evolve that, I think, will be really important.

WOLDT: Which is good. I mean, you own both entities, so it’s easy to make that happen. How about with third-party care?

STANIFORTH: I think there are things that everyone is trying to do, and I think even some of the work that we’re doing with Milliken Institute, I think there were some things we did a few years ago that were sort of before their time, that we are starting to talk about bringing back. We did all kinds of work with Rite Aid helper lines, where we were contracting with large HCOs in value-based care. We started talking about bringing that back. The problem we had was that when it actually came down to it, people didn’t want to pay. And so how do we make sure we can move that forward. But the principle worked really well; we had really incredible outcome.